https://earth-investment.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/PHOTO-2024-01-15-11-52-48-1500x842.jpg

https://earth-investment.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/PHOTO-2024-01-15-11-52-48-1500x842.jpg

For five consecutive years “license to operate” has dominated EY’s annual survey of the top 10 risks and opportunities in the mining industry and was noted in their 2024 report as becoming a long-term priority. It therefore came as a surprise, when organizing a site visit to the Zgounder silver mine in Morocco, when the company remarked that they had never been asked by investors to visit any of their sustainability projects before. Site visits tend to focus on the geology, the ore body and the economic parameters of a mining project and less on the people and environment in the area of influence of the mine.

The Zgounder silver mine is located approximately 265 kms east of Agadir in the Anti-Atlas Range. The mine is owned by Aya Gold & Silver Inc., a Canadian company who engage in the exploration, evaluation, and development of gold and silver deposits primarily.

To support social license to operate, mining companies are often under pressure to employ people from the surrounding communities. Oftentimes, though, these individuals lack the necessary, sometimes niche skills, required for employment. The company noted that a few of the workers hired for basic work were illiterate. There is a national literacy programme in place, but it doesn’t have the reach they hoped for in remote areas. As a result, a few months prior to the site visit, the company supported the set up of a literacy center for all in the village of Askaoun, around 7km south west of the mine, providing materials and paying the teacher who was selected with an agency together with the government. The project was met with significant interest, so that different classes were set up for community members of different age groups. When we visited, there was a class in progress for elderly women from the area.

Fig 1: “I don’t know….many, many years”, the lady replied when we asked her age. The elderly Moroccan lady from the central Anti-Atlas Mountains had recently learned how to write the letter “A” in Arabic and beamed with pride as she held up her chalk board.

Source: ERI

Nelson Mandela once said, “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.” Despite the time it takes to bear fruit, it provides the strongest foundation to lead people out of poverty which is seen as one of the major hindrances to sustainability. An interviewee once said “I struggle to feed my children. I don’t care if you chop down that tree.”

One of the concerns facing the industry is attracting talent with the necessary skills. In addition to some support in local schools, like providing school busses, and painting classrooms, the company noted the need to support sciences, which forms the basis of a number of jobs required for the mine. Nearly 67% of pupils in the area went on to study arts as their marks were not good enough for sciences. The mine therefore decided to support extra lessons in maths.

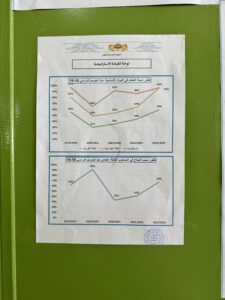

The following image shows the teacher in Agadir, connected virtually to the students via Yool (https://www.yool.education/), a tool that provides online courses. Every student has two hours of extra lessons per week. Since starting the project in 2023, the marks have improved substantially. The next step is to support the school in French and English. Currently the main languages are Arabic and, in this area more especially, Berber languages are spoken.

Fig 2 Initially the company bought computers, but the internet signal was too weak to carry individual computers. A group e-learning classroom structure was set up, which works well as shown in the increase in pass rate: blue line in the graph.

Source: ERI

The BBC reported that Morocco entered it’s sixth year of drought in 2024 making water a stressed, shared resource. The company commissioned an external study to see how much water draw they have from the catchment area, and this was calculated to be 6%.

To support the six villages surrounding the mine, boreholes were installed with solar pumps (fig 3). Water is pumped to a reservoir where villages have access to water. Each serves 30 households or 200 people. The borehole depicted below serves the village of Aolousse. Previously, water was collected by hand from surrounding springs.

Fig 3: Solar powered borehole to the aquifer serving the village of Aolousse.

Source: ERI

The “Life of Mine” can be explained as the number of years that mines operate, as long as it is profitable to extract the ore. As this time comes to an end, the workers and suppliers who serve the mine are left without a job, which is why an important social aspect of sustainability is the support of alternative livelihoods that can continue beyond the life of mine.

The Taliouine region, where the Zgounder mine is located , is known as the “capital for saffron”, an expensive spice, referred to as “red gold”. In 2023, the company set up a model training farm, which serves as a learning and collaborative platform to encourage small scale farming, supporting alternative livelihoods for the community.

The terraces as shown in figure 4 are each monitored and managed differently, showcasing different varieties and techniques for saffron cultivation.

Fig 4: The office next to the plantation, solar panels. In the background is the plantation showing the different study area terraces of the saffron plantation.

Source: ERI

Fig 5: A worker on site showing me the buried flower bulb. The bulb is hardy, perennial and provides flowers for around 5 years. Saffron could also naturalize in the area. The company set up the comprehensive irrigation system.

Source: ERI

Fig 6: The saffron flowers grow, bloom and can be harvested all within 2 months. The saffron threads are the stigma of the flower.

Source: ERI, Aya Gold & Silver

Fig 7: Here one of the ladies from the cooperative shows me some of their 2023 harvest.

Source: ERI

There are some limitations to site visits from a sustainability perspective. Language barriers can prevent direct communication with the community members, and access is sometimes prohibitive due to the remoteness of some assets.

Life and death are believed by Muslims to be in the hands of Allah. Despite religious views that the time one passes on is predetermined by God and safety precautions may be seen as meaningless, safety is of utmost priority. The company created a mine rescue and command center and were trained by a gentleman from Canada to form an emergency response team. Their 2023 sustainability report noted that they will soon have two female members on the emergency response team, the only women certified as such in Morocco. Safety and continual training is a fundamental part of mining operations.

Fig 8: Safety Training Room

Source: ERI

The company recently purchased a few air breathing system units that can work up to 4hrs underground. They are the first mine in Morocco to use these. Other mines in the area came to visit the setup at Zgounder with the intention to replicate it on their sites. The positive outcome is that all in the area are familiar with the same equipment and can support each other in an incident event, an excellent example of collaboration.

Fig 9: Air breathing system units recently purchased, aligned with other collaborating mines and the underground rescue truck.

Source: ERI

Fig 10: “Safety begins with me” – an omnipresent logo and reminder, seen everywhere on site. On buildings, in presentations (left), and on uniforms (right).

Source: ERI

In contrast, unrelated to the site visit and purely by chance, we visited a mine where it was unclear who the owner was in the Merzouga area. The mine was called “Mifir” which translates as the “mouth of the Tiger” and seemed to mine for zinc, barium, and silver ore. The locals sold minerals from the mine (and fossils from the area) calling it “mascara”. Work conditions were very primitive and dangerous. There was no signage, and no effective barricades. Small scale miner clothing was lying around in the vicinity of the vein that was being mined. This example demonstrates the stark contrast between mining responsibly and on a small scale with no resources.

Fig 11: Small scale mining along the vein (left), selling mined minerals and fossils from the area to tourists (middle), basic machinery in the background with no safety barriers (right).

Source: ERI

Fig 12: Basic machinery in small scale mining. In the background: excavator and basic machinery with a pully system lifting buckets of ore out of the ground. In the foreground: small scale miner’s clothes, plastic funnels, gloves and shoes left in the sand.

Source: ERI

When done responsibly, the mining industry can make a significant contribution to sustainable development. It provides local governments with royalties and taxes and employment opportunities to its citizens, increasing their social standing. Sustainable alternative livelihood opportunities can be created for the local community, as given in the saffron case study in this article, ensuring independence from employment in exhaustible mining activities, fighting poverty, and discouraging artisanal mining.