https://earth-investment.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Rankin-Inlet-Inuksuk_Quelle_Agnico-Eagle-Mines-1500x1000.jpg

https://earth-investment.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Rankin-Inlet-Inuksuk_Quelle_Agnico-Eagle-Mines-1500x1000.jpg

Critical Minerals on Indigenous Lands

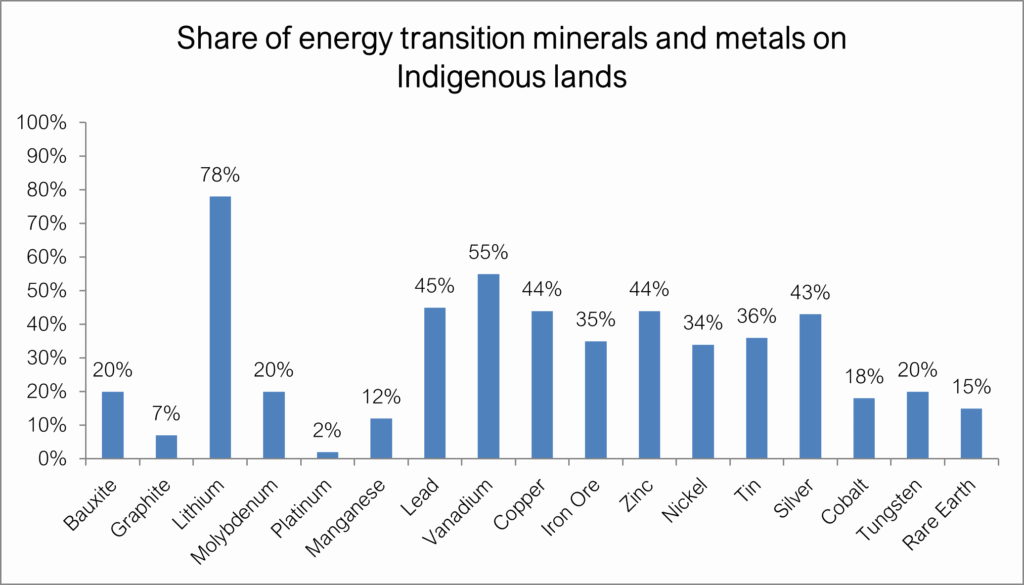

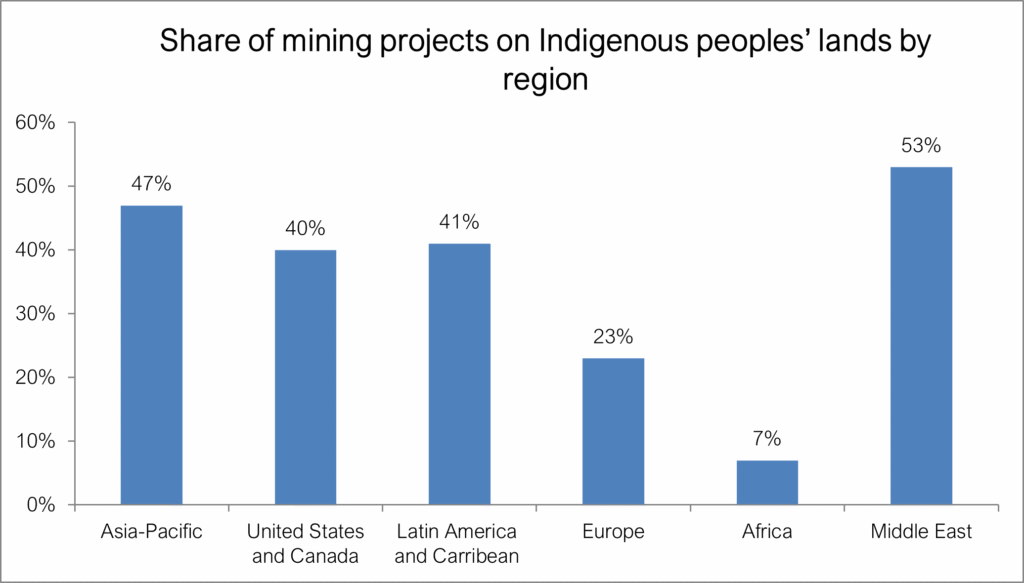

With the rapid expansion of renewable energy, the accelerated electrification of mobility, and the strong technologization of society, the demand for metals such as copper, nickel, zinc, and rare earths is increasing. The new energy carriers and technologies depend on mining projects, more than half of which are located on or near Indigenous-claimed land. This means that new mining projects are increasingly exposed to conflict potential for socio-economic or ecological reasons.

Demographic and Cultural Significance of Indigenous Peoples

Indigenous peoples are communities that identify themselves as having ancestral territories and that maintain their own social, political, and cultural institutions. They are not a homogeneous group: an estimated 476 million Indigenous people live in 90 countries worldwide. They make up less than five percent of the world’s population, but are disproportionately affected by poverty and speak a large portion of the world’s approximately 7,000 languages, spread across about 5,000 cultures. Many Indigenous communities maintain a close, often spiritual connection to land and waters, which are central to identity, food security (hunting, fishing, gathering, pastoralism), local economies, and the preservation of sacred sites and knowledge systems.

In the context of the energy transition and the rising demand for critical minerals, this reality intersects with growing project pipelines in resource-rich regions, as numerous mines are located on or near Indigenous land (see Fig. 1). This creates opportunities (e.g., income, infrastructure, education) but also risks (e.g., interference with land rights and culture, environmental burdens, unequal bargaining power). Sustainable cooperation therefore requires secure land and usage rights, reliable access to basic services, and early, clear, and respectful engagement.

Distribution of critical minerals in indigenous territories

Figure 1: Share of energy transition minerals and metals on Indigenous-claimed land

Figure 2: Share of mining projects on Indigenous peoples’ lands by region

Own illustration based on source data from: Owen, J.R., Kemp, D., Lechner, A.M., Harris, J., Zhang, R. & Lèbre, É. (2023): Energy transition minerals and their intersection with land-connected peoples. Nature Sustainability 6, 203–211. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-022-00994-6. Modification “Peasant” category excluded; showing “Indigenous only.” Dataset (UQ eSpace): Owen, J.R., Lèbre, É. & Kemp, D. (2022): Energy Transition Minerals (ETMs): A Global Dataset of Projects. The University of Queensland. https://doi.org/10.48610/12b9a6e. Reused with acknowledgement according to UQ eSpace.

Own illustration based on source data from: Owen, J.R., Kemp, D., Lechner, A.M., Harris, J., Zhang, R. & Lèbre, É. (2023): Energy transition minerals and their intersection with land-connected peoples. Nature Sustainability 6, 203–211. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-022-00994-6. Modification “Peasant” category excluded; showing “Indigenous only.” Dataset (UQ eSpace): Owen, J.R., Lèbre, É. & Kemp, D. (2022): Energy Transition Minerals (ETMs): A Global Dataset of Projects. The University of Queensland. https://doi.org/10.48610/12b9a6e. Reused with acknowledgement according to UQ eSpace.

Legal Framework

The rights of Indigenous peoples remain only partially enshrined in many countries today. For centuries, colonial legal doctrines such as terra nullius (Australia) and the Doctrine of Discovery (North America) served to dispossess Indigenous peoples by declaring land they inhabited as “no man’s land,” enabling its claim by European colonial powers. Only much later did landmark court rulings begin to break down these premises, such as Mabo (1992) in Australia, which rejected terra nullius.

Today, the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP, 2007) sets the global reference framework: self-determination, protection of lands, territories, and resources, and the principle of Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) for projects affecting Indigenous rights. UNDRIP is not directly legally binding under international law, but exerts influence through state-level implementation in national legislation and its incorporation into international standards (e.g., International Finance Corporation Performance Standards, OECD Guidelines), thereby indirectly obligating companies to comply.

In Canada, for example, UNDRIP has been incorporated into national law through Bill C-15, thus bridging to the constitutional framework of Section 35 of the Canadian Constitution Act of 1982, which protects the rights of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis. Bill C-15 also establishes a binding legal foundation ensuring that federal laws and regulations are consistent with UNDRIP, and requires the government, in collaboration with First Nations, Inuit, and the Métis Nation, to develop an action plan and provide regular progress reports. Key objectives include combating systemic racism, advancing self-determination, and recognizing FPIC in consultations with Indigenous peoples.

Economic Risks for Mining Companies

Environmental risks often act as triggers or accelerators of conflicts between local communities and mining companies. However, the deeper causes often lie in distributional issues and inadequate consultation. These structural problems weaken relationships between stakeholders and make escalation into confrontation more likely.

In a study on the cost-related and operational consequences of conflicts between extractive companies and local/Indigenous communities, Davis and Franks found that the most frequent impacts are production losses and delays. For a major project with US$3–5 billion in capex, each week of delay can cost around US$20 million (calculated on the project’s net present value), primarily due to lost revenues. Direct costs already arise during the exploration phase (e.g., idle drilling teams). In the construction phase, companies reported tens of millions of dollars in losses per day of delay. Reputational costs and impacts on share price due to project delays are not even included here.

This is precisely why clear state processes are needed. Rohitesh Dhawan, CEO of the industry association ICMM, emphasizes that governments must actively help secure local consent; mere state project approval is not sufficient if local support is lacking. In other words, the risks of non-sustainable consent are too costly—both economically and socially—to leave solely to negotiations between companies and communities. Governments should ensure FPIC and support industry in local consent processes. No mining project should proceed against local opposition based solely on government approval.

Potential for Sustainable Partnerships

Despite these challenges, there are overlaps between the goals of mining companies and Indigenous peoples. Many communities seek sustainable income sources, improved infrastructure, and educational opportunities, while mining companies are interested in regional stability, predictable project timelines, and secure access to resources. This common ground forms the basis for partnerships that can aim at effective cooperation.

Through Indigenous equity participation, communities become co-owners of projects, gain formal decision-making rights, and can systematically incorporate traditional knowledge into environmental and land management processes. This not only leads to stronger environmental protection measures but also to the development of independent revenue streams and significantly improved social outcomes for Indigenous communities—factors that simultaneously accelerate permitting processes and foster stable operating conditions.

Case Study: Reconciliation Action Plan of Agnico Eagle Mines

A successful example of cooperation is provided by Agnico Eagle Mines Limited, which in July 2024 published its first company-wide Reconciliation Action Plan (RAP), translating economic participation into measurable actions (including training, employment, supply chains). While Agnico Eagle has implemented various programs and initiatives benefiting Indigenous peoples for many years, the RAP represents an important step toward integrating these activities into a central, comprehensive strategy.

The plan encompasses seven areas of action, ranging from corporate governance to economic participation and environmental protection, and was developed in close coordination with more than 250 Indigenous and non-Indigenous stakeholders. The company emphasizes that Indigenous partners as suppliers and business partners are a central pillar. According to its own figures, Agnico Eagle invested around US$1.9 billion in locally sourced goods and services, about US$1 billion of which went to Indigenous businesses, thereby significantly strengthening regional value creation. The company believes that a well-designed platform for Indigenous engagement can help management teams build relationships with Indigenous suppliers and businesses and improve its social license to operate. At the same time, companies must navigate a delicate balance: involving Indigenous businesses and building regional value creation, while ensuring that “value for money” remains the benchmark of corporate procurement frameworks.

Case Study: Lawsuit Against the Pebble Project in Alaska

A second example comes from North America. In June 2024, Iliamna Natives Limited and the Alaska Peninsula Corporation, two Alaska Native Village Corporations, filed a lawsuit against the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). They argue that the EPA veto under Section 404(c) of the Clean Water Act jeopardizes their economic prospects, as they had concluded extensive service and infrastructure contracts with the Pebble Partnership.

The Pebble deposit lies on state land and is registered under the U.S. state of Alaska. In the early 2000s, the parent company of Pebble Partnership, Northern Dynasty Minerals Ltd., acquired mining rights and began exploration. Transport corridors partly cross lands transferred to Alaska Native Corporations under the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA), as well as private land.

In this ongoing conflict, affected communities point to potential jobs and revenues for local development projects, while the EPA’s final determination prioritizes the protection of salmon waters in Bristol Bay. The case illustrates that Indigenous actors are not only in opposition to planned projects but can also proactively cooperate contractually and exert legal influence on development and permitting steps.

Conclusion

A responsible mining industry that respects Indigenous land rights and seeks partnerships with Indigenous communities lays the foundation for long-term benefits and risk reduction for all parties involved. Early and effective engagement can establish Indigenous participation models, accelerate permitting for mining, energy, and infrastructure projects, and meet investors’ growing demands for transparency and consultation.

Such partnerships make a significant contribution to a stable operating and investment climate. The Earth Strategic Resources Fund specifically supports companies that implement these principles, thereby helping ensure that responsible resource extraction is not only ethically imperative but also economically promising.

Sources:

Woodley, M. und Donovan, B. (2024) ‘Unlocking Indigenous Potential in Mining Regions: From stakeholders to shareholders’. COGITO (OECD-Blog), 19. Januar. Online verfügbar unter: https://oecdcogito.blog/2024/01/19/unlocking-indigenous-potential-in-mining-regions-from-stakeholders-to-shareholders/ (Zugriff: 23.07.2025).

United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII) (2006) ‘Indigenous Peoples, Indigenous Voices: Fact Sheet 1 – Who are Indigenous Peoples?’ New York: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

United Nations (o. J.): International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples. Online verfügbar unter: https://www.un.org/en/observances/indigenous-day (Zugriff: 25.07.2025).

United Nations (o. J.): International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples. Online verfügbar unter: https://www.un.org/en/observances/indigenous-day (Zugriff: 25.07.2025).

United Nations (2007): United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. New York: United Nations.

Dr. Bryan Keon-Cohen (2025): The Mabo Case: From Terra Nullius to Native title Victoria Law Foundation, Victoria Law Foundation, S. 5.

Miller, Robert J. (2019): The Doctrine of Discovery: The International Law of Colonialism, The Indigenous Peoples’ Journal of Law, Culture & Resistance, 5(1), S. 35.

Dr. Bryan Keon-Cohen (2025): The Mabo Case: From Terra Nullius to Native title Victoria Law Foundation, Victoria Law Foundation, S. 5.

United Nations (2007): United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. New York: United Nations.

Department of Justice Canada (2021): United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act – Legislation. Online verfügbar unter: https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/declaration/legislation.html (Zugriff: 20.08.2025).

Department of Justice Canada (2021): Bill C-15: An Act respecting the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Online verfügbar unter: https://canada.justice.gc.ca/eng/trans/bm-mb/other-autre/c15/c15.html (Zugriff: 20.08.2025).

Davis, R. & Franks, D.M. (2014): Costs of Company–Community Conflict in the Extractive Sector. Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative Report No. 66, Harvard Kennedy School, Cambridge, MA., S. 8

Davis, R. & Franks, D.M. (2014): Costs of Company–Community Conflict in the Extractive Sector. Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative Report No. 66, Harvard Kennedy School, Cambridge, MA., S. 8

Davis, R. & Franks, D.M. (2014): Costs of Company–Community Conflict in the Extractive Sector. Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative Report No. 66, Harvard Kennedy School, Cambridge, MA., S. 19

Scheyder, E. (2024) ‘Governments must broker local support for mines, industry group says’. Reuters, 19. April. Online verfügbar unter: https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/official-governments-must-broker-local-support-mines-industry-group-says-2024-04-19 (Zugriff: 20.08.2025)

BMO (2024) Indigenous Engagement: Which TSX Companies Are Setting the Pace?

Agnico Eagle (o. J.): Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples. Online verfügbar unter: https://www.agnicoeagle.com/English/sustainability/social/reconciliation-with-indigenous-peoples/default.aspx (Zugriff: 27.07.2025).

Agnico Eagle (o. J.): Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples. Online verfügbar unter: https://www.agnicoeagle.com/English/sustainability/social/reconciliation-with-indigenous-peoples/default.aspx [abgerufen am 27.07.2025].

EPA (2023) Final Determination for Pebble Deposit Area (CWA § 404(c)). Verfügbar unter: https://www.epa.gov/bristolbay/final-determination-pebble-deposit-area (Zugriff: 19.08.2025).

Reuters (2024) ‘Alaska Natives sue EPA over Pebble mine veto, Northern Dynasty says’, Reuters, 26. Juni. Verfügbar unter: https://www.reuters.com/legal/alaska-natives-sue-epa-over-pebble-mine-veto-northern-dynasty-says-2024-06-26/ (Zugriff: 19.08.2025).

Alaska DNR (n. d.) Pebble Project – Alaska Division of Mining, Land, and Water. Verfügbar unter: https://dnr.alaska.gov/mlw/mining/large-mines/pebble/ (Zugriff: 19.08. 2025).

Harvard Environmental & Energy Law Program (EELP) (n. d.) Bristol Bay / Pebble Deposit Tracker. Verfügbar unter: https://eelp.law.harvard.edu/tracker/bristol-bay-pebble-deposit/ (Zugriff: 29.08.2025)

Alaska DNR (n. d.) Pebble Project – Alaska Division of Mining, Land, and Water. Verfügbar unter: https://dnr.alaska.gov/mlw/mining/large-mines/pebble/ (Zugriff: 19.08.2025).

EPA (2023) Final Determination for Pebble Deposit Area (CWA § 404(c)). Verfügbar unter: https://www.epa.gov/bristolbay/final-determination-pebble-deposit-area (Zugriff: 19.08.2025).

Reuters (2024) ‘Alaska Natives sue EPA over Pebble mine veto, Northern Dynasty says’, Reuters, 26. Juni. Verfügbar unter: https://www.reuters.com/legal/alaska-natives-sue-epa-over-pebble-mine-veto-northern-dynasty-says-2024-06-26/ (Zugriff: 19.08.2025).