Home » Insight » An Update on Mining in South Africa

We recently had the opportunity to visit Harmony Gold’s Mponeng Mine near Carletonville, including a trip to the deepest point of the mine – of any mine (3’891m). Having been innately involved with South African mining for the last three decades, this visit showcased how South African miners have – largely – successfully dealt with the increasing technical challenges.

Figure 1. ERI’s Christian Siebert at the deepest point on Mponeng Mine.

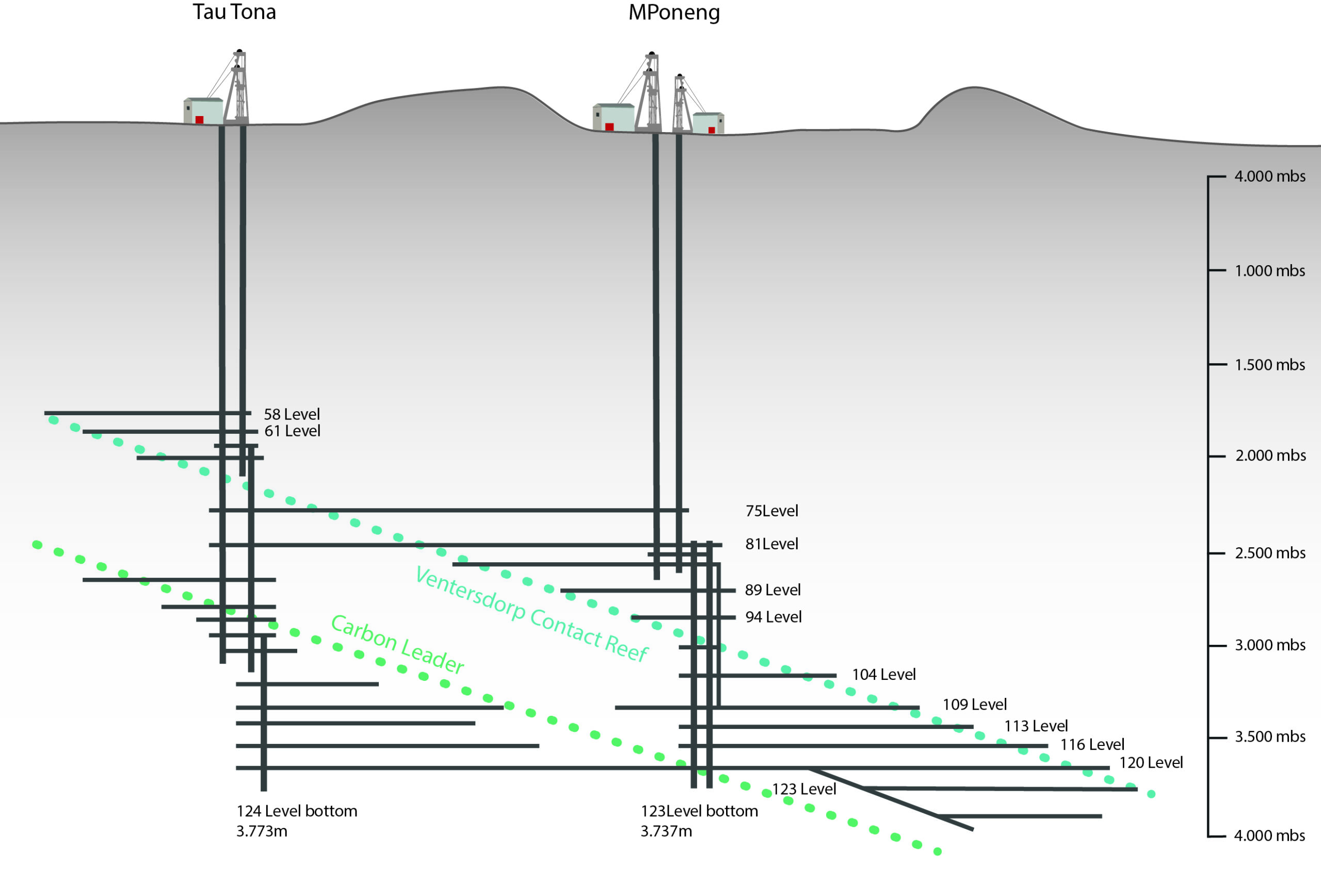

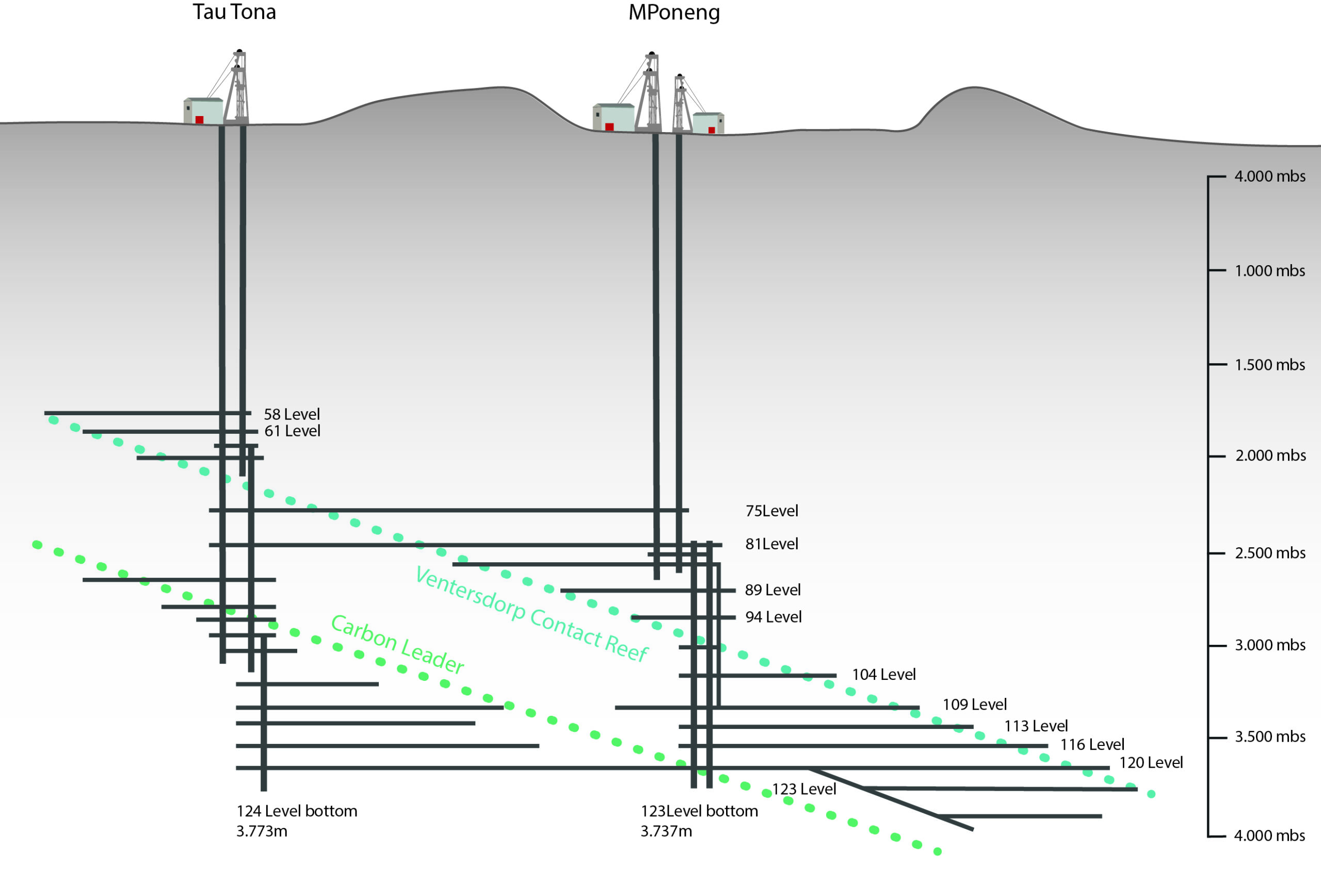

While a steeply weakening Rand and a strengthening dollar gold price have softened the impact of declining grades, the main technical challenges result from continuously mining deeper. Greater depth requires significant infrastructure to transport man, material and ore. In the case of Mponeng, this includes two surface shafts, three sub-shafts, and two quadruple declines. Each decline consists of a separate tunnel for a chairlift, a monorail for material and consumables, a conveyer for ore as well as a return airway.

Figure 2. Section of Mponeng’s and the adjoining Tau Tona’s infrastructure (Harmony Gold)

To compensate for the lengthy travel time to the working places, crews work 11-hour shifts. Two crews usually mine three panels to provide additional flexibility if one panel cannot be mined due to technical reasons. Two ice plants on surface provide the necessary cooling for the working places.

As the mining depth at Mponeng increases, so does the pressure in the virgin rock ahead of the working place (stope face). Due to the hard and brittle properties of the rock, the build-up in pressure increases the probability of pressure bursts at the face. These, and other seismic events like falls of ground (FOG), have to date accounted for 50% of the fatalities at Mponeng. To prevent pressure bursts, the rock ahead of the face is pre-conditioned or de-stressed. There are various ways of pre-conditioning, but at Mponeng they drill 2.4m long holes, 3m apart in centre of the face, halfway between the hanging wall and the footwall. These holes are then charged with explosives and detonated. The effectiveness of this procedure depends on the quality of execution; hence significant time is spent on training staff accordingly.

To avoid falls-of-ground, paste backfill is carried up to 4m from the face, in addition to installing roof bolts and wire mesh in the hanging wall. Paste backfill combines the tailings (waste from the processing plant where the gold is extracted from the ore) with cement. This is then pumped into the excavation left from extracting ore.

The following picture shows a typical stope at Mponeng, where the ore is extracted. On the left is the face of the reef (orebody), and on the right, one can see the paste backfill. In the space between, which is additionally supported by timber ‘pegs’, rock bolts and mesh wire, the miners carry out their work.

Figure 3. A typical stope at Mponeng (Harmony Gold).

All this, however, comes at a cost. Nonetheless, Mponeng is forecasting All-In Sustaining Costs (AISC, the cost of maintaining gold output at current levels) of USD1’400 – 1’500/oz for 2023. Even with a reserve grade of 8.76g/t Au, considering the scale of Mponeng’s infrastructure and that mining takes place at depths of 3’170 – 3’740m, this is a commendable achievement.

But, whilst taking on technical challenges in their stride, South African miners face stronger headwinds that pose an even bigger threat to the sustainability of the industry. The desolate state of Eskom (South Africa’s electricity utility) and the resultant load shedding are chief among them. Generally, miners are exempt from load shedding but have to deal with load curtailment. This means that they need to periodically reduce their power consumption by, for example, switching off surface equipment like concentrators. By prioritising underground ore production, also for safety reasons, they can later catch up on the last output.

The overall impact on production for gold miners has to date been limited; it has, however, affected efficiencies and, thereby, costs.

Platinum Group Miners (PGM) miners, on the other hand, have, according to World Platinum Investment Council, seen a 14% drop in output for the first quarter, around half of which was related to load curtailment. PGM miners are more affected than gold miners due to the power-intensive refining of the metal.

While Eskom announced implementing Stage 8 load shedding this winter, meaning that consumers face 12 hours a day without electricity, to date, this has not materialized. In fact, the situation appears to have improved after the government signed an electricity supply deal with Mozambique.

It remains to be seen how sustainable the situation is and whether the government can provide further improvements. Either way, load shedding and curtailment are not going to be entirely resolved in the near term. And as if this wasn’t enough, the situation is exacerbated by the syndicated theft of copper cables. As stated by Sibanye-Stillwater in the Q1 results, the PGM metals producer lost 5,200 oz of 4E PGMs due to cable theft compared to load curtailment losses of 5,120 oz.

Furthermore, Transnet, the state-owned company that owns the country’s railway, ports and pipeline infrastructure, suffers from a maintenance backlog and locomotive shortages. As a result, coal exports from Richards Bay have dropped by 20% compared to last year.

The mining license cadastre has also long been in disarray, and junior miners and explorers are faced with a huge backlog of applications for prospecting and mining licenses. After initially insisting on its own bespoke solution, the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy (DMRE) has finally agreed to put out a tender for a new system. It appears a new vendor will be appointed in July, but it will take some time to work through the backlog.

Finally, there is the never-ending feud between the government and mining companies over South African mining legislation. Whilst the government pushes for higher BEE shareholdings, the industry fights for regulatory certainty and security of tenure. Recently the High Court came to the miners’ aid by ruling that the 2018 Mining Charter was an instrument of policy and does not entitle the government to make laws. More importantly, the court endorsed the “once empowered, always empowered” principle.

So, is it best for investors to entirely avoid the sector? Not so, in our view. For one, most of the majors provide excellent ESG credentials. Harmony Gold, for example, will install a total of 223MW of solar energy in a three-phased approach by 2026. While a base load from Eskom will still be required, solar energy will reduce the impact of load curtailment on output and efficiencies. Similar strategies are being pursued by, to name a few, Gold Fields (40MW at South Deep) and Anglo American Platinum (100MW by 2024). Aside from the environmental benefits, these solar projects also create additional jobs in a country with an unemployment rate (> 30%) that is among the highest in the world.

In the context of ESG, it is also worth noting that 30% of the underground workforce at Mponeng are women.

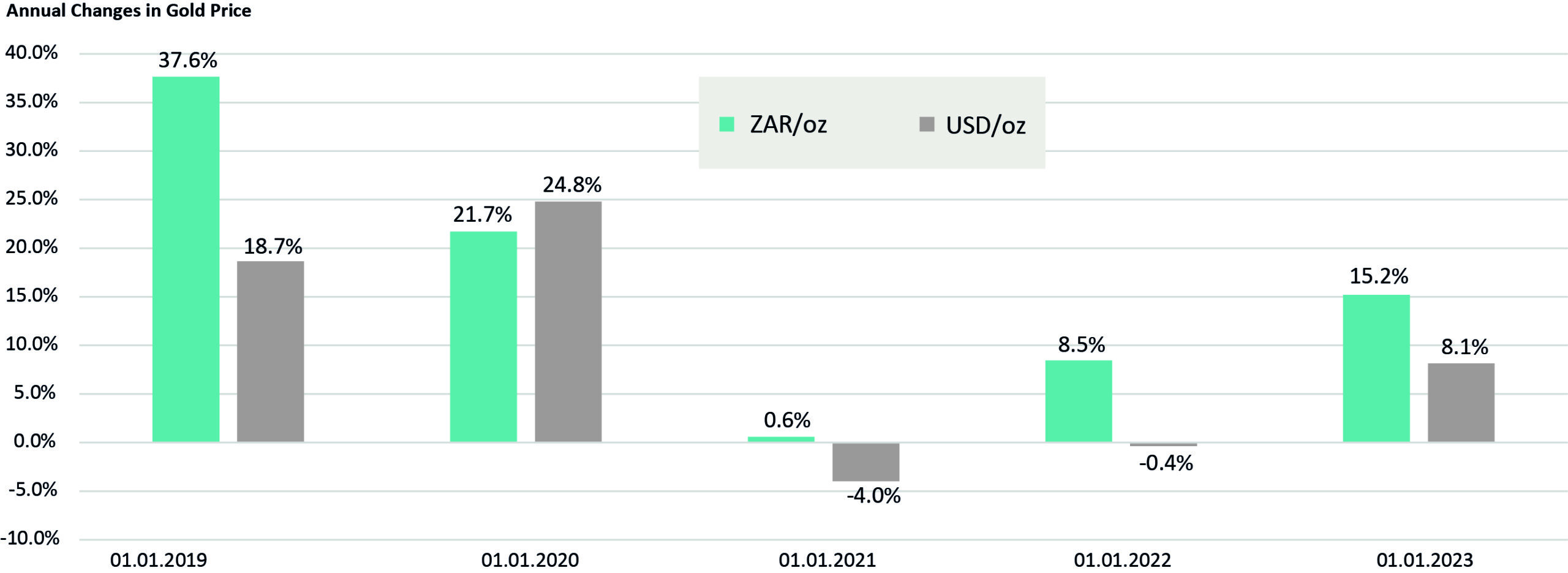

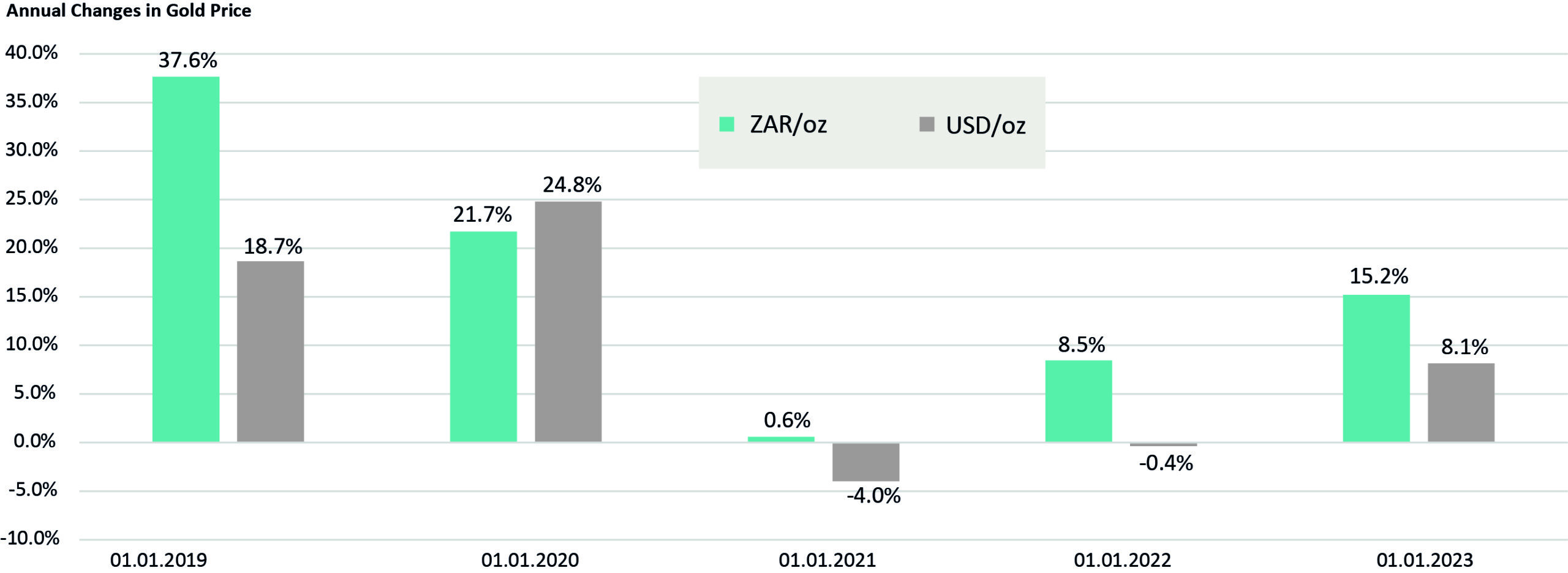

But what South African miners offer investors most of all is leverage. The high cost base provides excellent leverage to the USD gold price and to a weakening Rand (ZAR). As seen in the chart below, in 2022, the Rand gold price increased by 8.5% versus a flat dollar price. And in 2023 to date, the gold price in Rand has increased by 15% versus an increase of 8% in dollar terms.

Whilst inflationary pressures are high in South Africa (7% in 2022), cash operating margins for gold miners have still increased by 64% from USD275/oz in 2022 to USD451/oz in 2023 YTD.

Figure 4. Changes in the ZAR gold price vs. the USD price (S&P Global)

Operational risks are, in our view, also manageable, with the issues around load shedding and load curtailment, are often exaggerated in the press. Safety standards and performance have also vastly improved over recent years. The big unknown remains legislative risk, but here also, the last years have seen more noise and less action.

Therefore, at the right time, there is always a case to be made for investing in the South African mining sector. Harmony Gold’s share price, for example, thanks to strong operational performance and excellent leverage to gold, increased by 43% YTD, peaking at a plus of 67% in May.

Globally increasing geopolitical and operational risks to mining and exploration put the risk for the South African mining industry into perspective. Established producers such as Harmony Gold could therefore again be the focus of investors, despite the challenging political developments in South Africa.